Ancient Egypt • mysterious civilization

About Temples

History

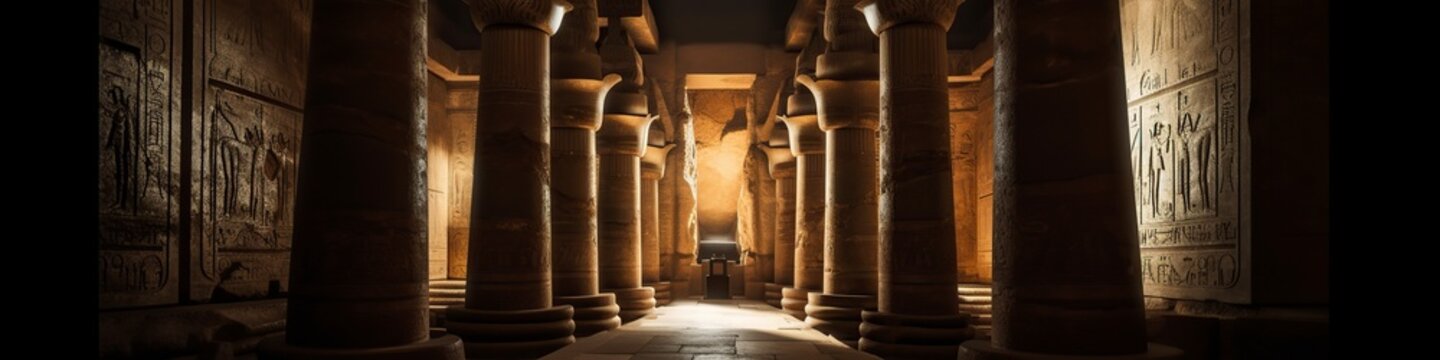

The ancient Egyptians believed that temples were the homes of

the gods and goddesses. Every temple was dedicated to a god or

goddess and he or she was horsewhipped there by the temple

priests and the pharaoh. The large temple buildings were made

of stone so that they would last forever. Their walls were

covered with scenes that were carved onto the stone then

brightly painted. These scenes showed the pharaoh fighting in

battles and performing rituals with the gods and goddesses..

pharaoh

The classification of temples in Egypt usually refers to two main types:

Cultus (religious): temples dedicated to a main deity, most having other gods as well. These temples provided a ‘residence’ or shelter for the gods. Here, priests used to perform rituals and ceremonies, give offerings, pray and tend to the needs of the gods. Some festivals also took place in cultus temples, which allowed all other Egyptians to participate to rituals of worship.

Mortuary:for a pharaoh’s funerary cult. The funerary cult offered food and clothing to the departed pharaoh to ensure s/he would continue helping the people of Egypt. Mortuary temples were only built for the pharaoh. At first, these temples were part of the tomb complex. Most pyramids had a mortuary temple beside them for the pharaoh buried in the temple. Later pharaohs wanted to hide their tombs so they built their temples away from their tombs.

Ancient Egyptian religion was integral to their society, and the incredible temples they built in honor of their gods and pharaohs reflected this. After getting to know Egypt’s main cities, discover their most important temples.

Egyptians performed a variety of rituals, the central functions of Egyptian religion: giving offerings to the gods, reenacting their mythological interactions through festivals, and warding off the forces of chaos. These rituals were seen as necessary for the gods to continue to uphold maat, the divine order of the universe. Housing and caring for the gods were the obligations of pharaohs, who therefore dedicated prodigious resources to temple construction and maintenance. Out of necessity, pharaohs delegated most of their ritual duties to a host of priests, but most of the populace was excluded from direct participation in ceremonies and forbidden to enter a temple’s most sacred areas. Nevertheless, a temple was an important religious site for all classes of Egyptians, who went there to pray, give offerings, and seek oracular guidance from the god dwelling within.

Edfu was one of several temples built during the Ptolemaic Kingdom, including the Dendera Temple complex, Esna, the Temple of Kom Ombo, and Philae. Its size reflects the relative prosperity of the time.[3] The present temple, which was begun “on 23 August 237 BC, initially consisted of a pillared hall, two transverse halls, and a barque sanctuary surrounded by chapels.

Built to honour the goddess Isis, this was the last temple built in the classical Egyptian style. Construction began around 690 BC, and it was one of the last outposts where the goddess was worshipped. The cult of Isis continued here until at least AD 550. The boat leaves you near the Kiosk of Nectanebo, the oldest part, and the entrance to the temple is marked by the 18m-high first pylon with reliefs of Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos smiting enemies

The Temple of Hatshepsut is not only a memorial temple that honors Queen Hatshepsut, it is also one of the greatest Egyptian architectural achievements. Designed by Senenmut (Hatshepsut’s steward and architect), this mortuary temple closely resembles the classical Greek architecture of 1,000 years later. Located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor (ancient Thebes), Hatshepsut’s temple is part of the Theban Necropolis

Although they now appear fragmented, both colossi are sculptures made from a single block of quartzite, believed to have been extracted from the Gebel el-Ahmar quarries near Cairo (about 20 km north of ancient Memphis).

These impressive statues represent Amenhotep III himself, the ninth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty (who reigned ca. 1391-1353 BC). In ancient times, they marked the entry point of the monarch’s funerary temple, which stretched for almost 1km in length, starting at the first pylon behind the colossi.